During those dreadful COVID years I became disillusioned with living in an apartment, the constant turnover of renters/neighbours, sharing the common areas and bins with people who just don’t ‘get’ or respect communal living. One fine autumn morning in 2020 at the height of the pandemic, a chance meeting with an estate agent in the hallway turned into a pure serendipitous encounter. It was the beginning of a journey which turned out to be the start of preparations for the next step in my life journey, Phase Three. The estate agent reassured me that I would have no problem in selling the apartment, so after a couple of false starts, the sale went through and I found myself moving a few kilometres down the road to a little bungalow where I found myself alongside neighbours; the kind who took in the bins when I was travelling and where we could swap hall door keys for cases of emergency. I had found my tribe. On one side I have a couple who are of similar age and on the other side of my new home, a young couple who were full of joie de vie, I couldn’t have knit better neighbours.

Moving on

Now almost five years on life continues, albeit with a slower pace than the heady days working with the United Nations. I still travel abroad for work when contracts become available, and when tides permit, summer or winter, I walk across the road for a sea swim off the Bull Wall, take in some music gigs, theatre nights and generally enjoy life. I joined a local over-55s Pilates class to improve my flexibility and maintain fitness. Last summer, the instructor had us lying on our side, balanced with one arm firmly planted on the floor and she requested that we lift our top leg. This bit was easy peasie; but then she suggested we lift the leg on the floor to meet the raised leg. To my horror, try as I might, my right leg wouldn’t budge. It could have been super-glued to the ground there was such little movement. It was the only symptom that indicated I required a replacement hip. Since my new left hip replacement 10 years previously I had continued doing the physio exercises, so I was gobsmacked when the orthopaedic surgeon informed me that if I had ignored the signs for another six months, I wouldn’t be able to walk such was the poor condition of the hip. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not moaning… shit happens once you reach a certain age and the years of enjoying life and giving it my all, has taken a not unexpected toll. However, for once in my life I was organised and when I moved into my little house, the Phase Three groundworks were put in place with alterations for the inevitable.

I had no trepidation about checking into hospital on 1 July to undergo surgery. I knew what to expect and was mentally prepared for the post-surgery recovery. On the day after surgery, the hospital physio came by to ensure I could climb and descend stairs without putting too much pressure on the hip. I don’t believe he was that long at the job, most likely just qualified. I had to stand holding a bar on the wall and swing my leg sideways. Not an issues with the left leg, but the right leg was sweeping the floor and in my innocence I believed that there was a building error in the way the floor was laid which caused a slant. It turns out that my operated leg is now 5 mm longer, which is, by all accounts, a common occurrence after hip surgery. Who knew? As I expected, I couldn’t bend down for several weeks or the hip would pop and so I had to employ the use of a ‘picker-upper’ that never seemed to be in the right room or the right place, when it was required. Being inherently lazy (and I like to think I’m creative about it), I learned to slide the operated hip behind me as I attempted to pick things up from the floor. If I forgot to bring the implement into the bathroom, putting on underwear could be compared to a rodeo rider trying to lasso a calf as I attempt to get the leg opening of my pants onto the foot of my operated leg. If the picker-upper made it into the bathroom, I was like a crane driver hovering, trying to dump a load of bricks or whatever, on to the correct spot. I became an expert in hooking things onto the end section of the crutch and flinging the item onto a higher surface. Terrified to bend down, I had to visit a chiropodist to cut my toe nails, which came possible when I could drive again week four post-surgery.

Spine-less

Prior to the whole shenanigans of the hip episode, I was on a mission to the Philippines as an election observer. I was still on a training course in Manila when I received a phone call from an Irish number. My thrifty-self went into action, at €3 a minute to receive a phone call, I almost gagged when a spine surgeon’s assistant began babbling something about an MRI result sent by the hip-man to the spine-man’s office and I needed an appointment. The assistant spoke about a spine surgeon, not a spine specialist, or a spine doctor, but a surgeon. For the next six weeks of the mission I imagined all sorts of doomsday scenarios as to why a spine surgeon would want to see me. Despite my imagination going into overdrive, I stubbornly sought out my favourite Japanese massage chain in Manila, Karuda. I always like to see qualification certificates hanging on the wall when I go for a massage, and I knew from previous visits that the staff are particularly well trained, which is reflected in what are considered to be outrageous charges in the Philippines! The treatment is around €30 for a body alignment, in comparison to having a ‘masseuse’ on the beach walk over your back for as little as the equivalent of €5. I didn’t realise when I was having the treatment that the cause of the excruciating pain in my back could be connected to why the spine-man wanted to see me. (If I was writing in emojis, I would include an eye roll and a hand over forehead here). However painful the massage, at least I had good circulation prior to taking a 20-hour flight back home.

On my return and before the new hip was installed I visited the spine-man. The surgery was optional, he announced. However, there was a caveat; my L3 and L5 (I think) were in trouble, and it was my choice whether I looked forward to a quality of life in the Third Phase, or without surgery I was guaranteed zero quality of life and would become incontinent. It was a no brainer and so, 10 weeks post hip surgery, I had my lower back decompressed and spine shaved to open the spinal canal. Just two days in hospital and then discharged on day three. You couldn’t exactly describe me as the most patient patient. Between the hip and the spine, everything was taking three times as long and some tasks were just impossible. Luckily I took a decision earlier in the year to have the bathroom gutted, by removing the bath and installing a walk-in shower. The bathroom was totally revamped in anticipation of growing older, I just didn’t expect older age to arrive less than six months later.

Return to the Philippines

I was very glad that I had packed in some travel in the first half of 2025 before undertaking the surgery and it was really interesting to revisit the Philippines 11 years since my last sojourn there. I was part of an election observation mission and the participants underwent a week’s training in Makati before our departure to the field. It was good to revisit my old stomping grounds, staying in a hotel about 20 minutes from the building where I once worked. I chased down a few friends/former colleagues to catch up and took an opportunity to pay a visit to the People’s Palace, located in Green Belt III where they serve the best pomelo and prawn salad, that never fails to please the palate. Many the times I tried to recreate the dish at home, paying a small fortune for a pomelo, but I never came close to the dish served up in the People’s Palace. Green Belt hasn’t changed much either, full of designer shops catering to the wealthy who can be found swanning around with poodles in nappies (diapers).

Disappointingly, not a lot has changed in terms of lifting people out of poverty, improving road transport, price increases or a greater awareness of diet and healthy eating. The Philippines is located in the Ring of Fire, an area in South East Asia prone to extreme weather events with several typhoons each year alongside frequent earthquakesre and active volcanos. There are still millions of vulnerable Filipinos, many in rural areas who live in shacks rather than well built homes, working in poorly paid jobs just about making enough to survive. And then there is the opposite end of the scale, the wealthy dynasties, the likes of Marcos family and the elite classes, manily land owners, business people and politicians. A small example is the the cost of a cup of coffee which is almost as expensive as in Ireland. Speciality coffee shops are as ubiquitous as mosquitos and prices as high as €3+ for an Americano. The most common variety available to the less wealthy is instant coffee and as a coffee snob, I rather drink a cup of tar than instant coffee.

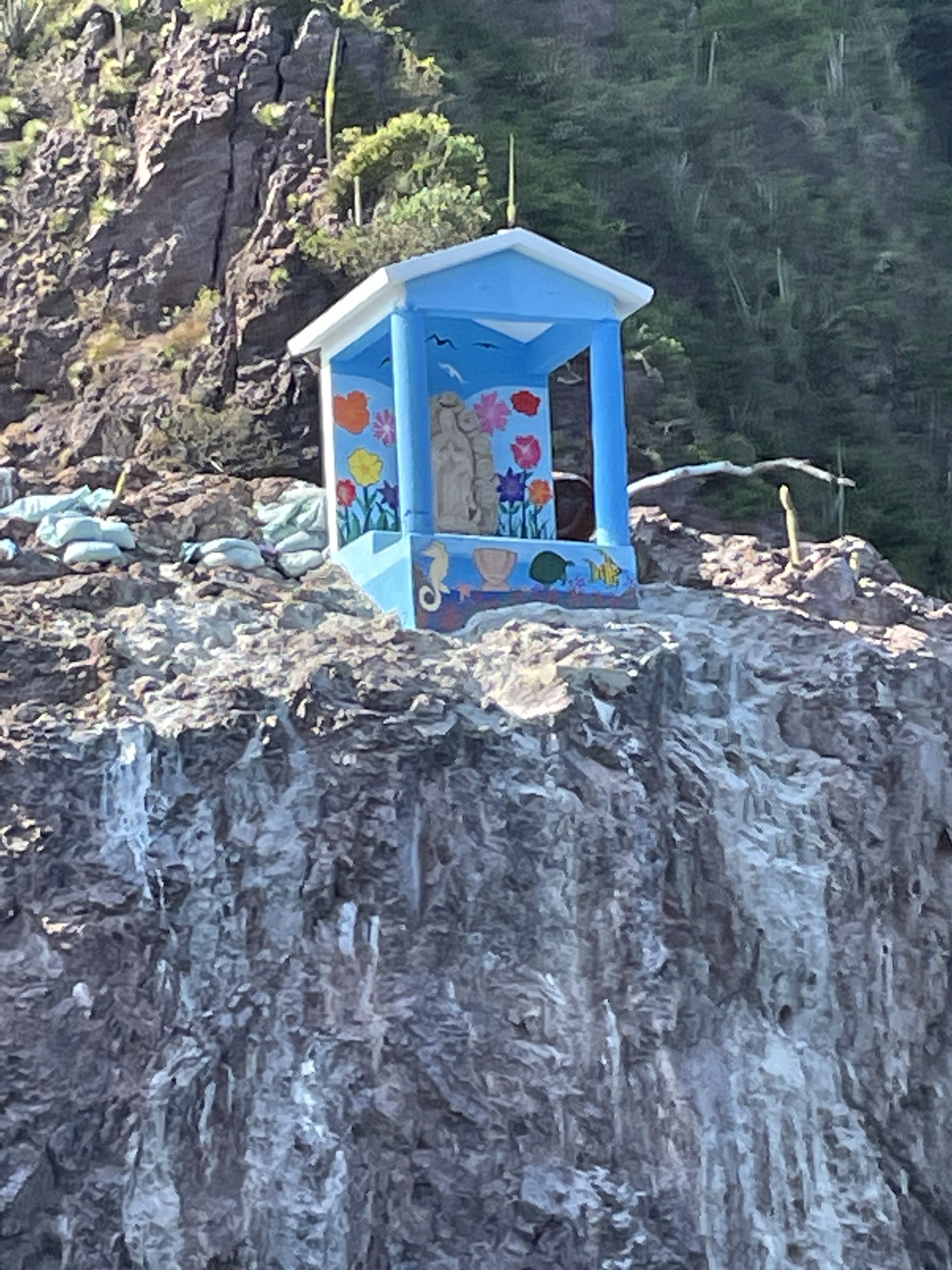

In terms of religious belief, the Philippines remains a mostly deeply Catholic country, so much so that we came across a chapel in a local public office, should you feel the need to redeem your soul in the middle of the work day.

Metro Manila is the seat of the government and Manila itself is made up of a series of cities, divided into 17 local government units, 16 of which are cities namely, Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, Valenzuela Quezon City (the most populus), Marikina, Pasig, Taguig, Makati, Mandaluyong, San Juan, Pasay, Parañaque, Las Piñas, Muntilupa and Pateros as the lone municipality. When I lived in Makati, the wealthy area of Manila, the traffic was impossible and I was lucky to be able to afford to live down the road from the office, so could walk to work. Crossing the city can take many hours, and I didn’t see any signs of extending the outdated and overcrowded metro line. Most workers coming into the city for work rely on public busses, called jeepneys. Jeepneys originate from the American colonial- period where they are used as shared taxis. These evolved to modified imported cars with attached carriages in the 1930s and served as cheap passenger utility vehicles. As of 2022, there were an estimated 600,000 drivers nationwide dependent on driving jeepneys for their livelihood and in Metro Manila an estimated 9 million commuters use jeepneys each day. Indeed, the traffic issues are not exclusive to Manila. For the election mission I was based in Tagaytay just 50 kilometres outside Makati and travelling to visit the electoral areas took hours each day, such was the volume of traffic on the roads.

Zero improvements in traffic management were made in the years since my previous visit, and sadly neither has the eating habits of the locals. According to the latest World Health Organisation nearly four in 10 Filipino adults and one in 10 children are classified as overweight or obese. The consumption of sugary drinks, fast and ultra processed food, alongside limited access to nutritious food contribute to the increasing cases of Type 2 diabetes. The pervasive fast food outlets are rife and to be found on every street. Try eating in Jolly Bees and you could be eating chicken or beef, it’s impossible to tell the difference. A McDonald’s breakfast is a regular morning ritual in the Philippines and there are zero healthy options in the fast food outlets which mostly offer highly processed food, full of empty calories. Shaky’s is the local pizza parlour and probably the healthiest of the fast food joints, if indeed, you could call any of them healthy. The best option for wholesome food is in the Makati malls, or if you’re lucky enough to be near the coast, there is a fantastic and plentiful selection of fresh fish.

All in all 2025 was a busy and interesting year, but I was glad to see the back of it and so with a new hip and a straight back, let’s see what’s in store for 2026, so far it’s looking good.

No AI used in this manuscript.